Figure 1: Lai Wenchi speaks at the conference in Taipei; Photo: Conor Stuart.

As the cost of entry for broadcasting has decreased with the onset of the internet era, the sheer amount of broadcast content has risen, along with the accompanying risk of copyright infringement. With the popularity of real-time Facebook Live broadcasts, there is less opportunity for pre-screening of output, and therefore a greater risk that broadcasts will contain copyrighted content without first having sought the permission of the copyright holders.

Wenchi Lai, an attorney with InfoShare Tech Law Office, was recently invited by the Taiwan Intellectual Property Office (TIPO) to give a speech on the copyright issues caused by the rise of new media, and he opened by stating, “Everytime I open Facebook, I don’t even have to scroll down to see numerous examples of copyright infringement!”.

In his speech, Lai pointed to several copyright issues in Taiwan.

Facebook ‘Public’ Pictures

The first issue involves the use of Facebook photos which are set to “public”. A photo of local Taiwanese celebrity, Cheng Chia-chun, was published on her Facebook as a “public photo”. The photo was then used on a third-party app which provided risque pictures of female celebrities to users on a daily basis. Cheng Chia-chun attempted to sue Lin Chi-chieh, the developer behind the Curator app, for using the photo she had published on Facebook. Although ultimately, the case was thrown out, the case did not actually address the issue of whether setting photos to “public” cedes any copyright claim, because neither Cheng, nor her agency, could prove their ownership of the picture in question. However, the throwing out of the case has led many people to believe that pictures that are set to “public” on Facebook are fair game for any purpose, a misunderstanding that has increased the risk of copyright infringement, according to Lai.

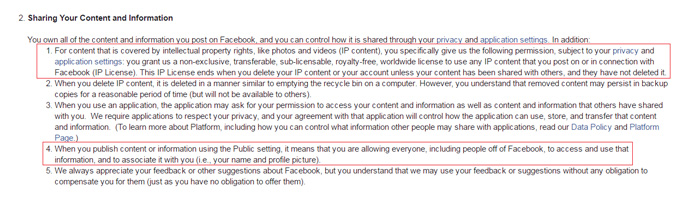

Article 2.1 of Facebook’s Terms states:

“For content that is covered by intellectual property rights, like photos and videos (IP content), you specifically give us the following permission, subject to your privacy and application settings: you grant us a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide license to use any IP content that you post on or in connection with Facebook (IP License). This IP License ends when you delete your IP content or your account unless your content has been shared with others, and they have not deleted it.”

Lai stated that from the wording it appears Article 2.1 only grants a license to user generated content to Facebook itself, and as soon as users delete content or their account, the license ends.

Many internet users have the false impression that any photo or video set to public can be used in any manner, as Article 2.4 of Facebook’s Terms, might suggest:

“When you publish content or information using the Public setting, it means that you are allowing everyone, including people off of Facebook, to access and use that information, and to associate it with you (i.e., your name and profile picture).”

Although this wording is vague enough to suggest a broader scope of use, in an appeal in a 2015 criminal intellectual property case at the Taiwan Intellectual Property Court (2015 Criminal Intellectual Property Basic Appeal No. 18), involving a woman who had used a photograph published on a company’s Facebook Page as an advertisement for her slimming club on Facebook, the judgement differentiated the terms “content” and “information”, suggesting that the third-party use mentioned in Article 2.4 only applies to “information”, specifically one’s public profile picture and full name, whereas the “content” is only licensed to Facebook itself.

Figure 2: Article 2 of Facebook's Terms

Live Broadcasts

Live broadcasting has become particularly en vogue of late, with Facebook, Youtube and Weibo all launching related services. However when generating content, whether it be gamecasting, performance or singing, it’s very hard for an individual to resolve license issues in the manner of a television production company, and they can only try their best to avoid copyrighted content, which can be quite difficult in a live context. Lai stated that many live broadcasters attract fans by performing popular songs, and even though they’re performing in their home, this still constitutes temporary reproduction of lyrics. It is also quite difficult to assert “fair use”, as broadcasters would at least need a public transmission license from the rights holder in this example; if a copy of the live broadcast is then published for repeat viewing, this could even require a reproduction license.

As well as popular songs, live broadcasts of eSports and gaming are also popular. So much so that Twitter recently announced that it’s teaming up with eSports firms ESL and DreamHack on a streaming deal. Although live streaming of games generally requires a license from the game maker, many individuals don’t get permission from the rights holders before they stream their content. Often it’s just because these kinds of videos help to sell games that there haven’t been any cases forbidding the practice so far.

Youtube Link Sharing and Fair Use

As the internet ecosystem has developed, there has been an increasing blur between the private and the public spheres. However, unless the use of the copyright of others is covered by the “fair use” as laid out in Article 44-65 of the Copyright Act, a license must be sought from the rights holder before use. For example, sharing a link to a film on Youtube to a friend through messaging app Line can also constitute copyright infringement, according to an August 28, 2014, clarification from the Taiwan Intellectual Property Office, if the person who provides the link is aware that the link leads to an unauthorized copy of the film.

Copyright legislation has had to adapt to the way the internet works, especially with the advent of websites like Youtube, on which much of the content is claimed to be “fair use” adaptations of the work of others.

From the world-renowned Pewdiepie and H3h3 Productions, to their local equivalents, such as Taiwan’s Tsai A-ga or AMoGood, many of these creators make videos which feature the work of others in addition to their own commentary, which they suggest creates new value. For example, Tsai A-ga filmed an alternative video to the theme song of the 2011 movie You Are the Apple of My Eye, ‘Those Years’, sung by Chinese singer Hu Xia, composed by Mitsutoshi Kimura, with lyrics by Giddens Ko.

AMoGood uses satire in reducing the plot of films and TV series into short summaries. These are structured using clips from the original movie, with a satirical narration from AMoGood dubbed over the top.

Does this constitute copyright infringement? What would happen if one or more of the rights holders decided to sue?

In a previous article for our Chinese-language sister newsletter, Quincey Chen, an assistant professor at the Graduate Institute of Technology of National Chengchi University, assessed the chances of AMoGood in asserting a fair use defense on the basis of the four factors on which fair use is to be judged listed in the Copyright Act, as follows:

- The purposes and nature of the exploitation, including whether such exploitation is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes.

- The nature of the work.

- The amount and substantiality of the portion exploited in relation to the work as a whole.

- Effect of the exploitation on the work's current and potential market value.

Although each individual case has to be judged on its own merits, Chen suggested that the outlook is not good for AMoGood should he be sued for copyright infringement, given that he likely profits from videos through advertising revenue (Factor 1), that the original work is creative (Factor 2), that AMoGood essentially provides an abridged version of the film (Factor 3) and that the videos can be seen as replacements for the original work given that they give details of the major characters and plot twists and could put people off actually seeing the original film (Factor 4). Although there has yet to be legal action against his channels, they have repeatedly been reported for copyright infringement and have previously been suspended by Youtube.

The process of defending oneself against a copyright infringement suit can be long and expensive and holds susbstantial risk, given the subjective language that enshrines the “fair use” clauses in both Taiwan, the US and elsewhere.

The couple behind the popular H3h3 Productions channel, for example, found themselves being sued by a fellow Youtuber recently, and they claim to have already spent upwards of US$150,000 thus far, with legal fees of around US$50,000 for one month’s work. As the creators behind the channel state, they are relatively lucky in that they have been able to afford the costs of defending themselves thus far, due to donations from fans and having resources of their own. Not all Youtubers are so fortunate however, and the cost of defending oneself against fair use can dwarf the initial settlement offer. This leaves a lot of ground open for disreputable “copyright trolls” to make a quick buck, forcing people to settle in cases rather than fighting a prolonged legal battle.

Profiting from a work can also be a nuanced term, in that advertising revenue often isn’t the only source of income for online video producers, many of whom have Patreon or WeChat accounts, whereby people give donations to creative people they enjoy the work of. In this case it’s hard to know how much any one video might have spurred people to donate funds.

Newer territories still, such as 3D live broadcast and VR gaming will also raise certain issues. If you want to create a virtual table to feature in a game, for example, and you 3D scan a table and reproduce it virtually, this could possibly constitute copyright infringement, according to Lai.

|

|

| Author: |

Conor Stuart |

| Current Post: |

Senior Editor, IP Observer |

| Education: |

MA Taiwanese Literature, National Taiwan University

BA Chinese and Spanish, Leeds University, UK |

| Experience: |

Translator/Editor, Want China Times

Editor, Erenlai Magazine |

|

|

|

| Facebook |

|

Follow the IP Observer on our FB Page |

|

|

|

|

|

|